Cracking Up: On I Saw the TV Glow, The Influence of Twin Peaks: The Return, and Never Leaving Your Shell

Beyond Trans Authorship, Jane Schoenbrun's film offers insight into pre-transition anxieties

Disclaimer: If you did not know already, Corpses, Fools, and Monsters: The History and Future of Transness in Cinema, the book I co-wrote with Willow Maclay is available to pre-order ahead of its July 9th release date. Willow also wrote an excellent piece on I Saw the TV Glow and interviewed writer-director Jane Schoenbrun for Film Comment when it debuted at the Sundance Film Festival. Spoilers ahead for both The Beast, Twin Peaks: The Return, and I Saw the TV Glow. Also CW on with discussion on suicide.

I. Prelude

Writing personal essays is so gauche and yet, here I am doing it. It is a very ‘Transition Year 1’ level of cringe that I firmly have rolled back on ever willingly doing ever again, even with the prospect of having a freelance check waved in my face. Part of this is regret in how much I exposed a lot about myself writing through a lot of personal turmoil in 2017 (I consider Transition Year 1 as the first year I used hormones) and being my most visible after building an online following through years of pseudonymity. Add in my attempts to drop alcohol that I still am making a living amends for and you got one hell of a Saturn Return. I sometimes forget I also got in a car accident and mugged because that same year- there was just a lot happening. My therapist would describe my plunge into taking HRT as “learning to swim by jumping into the deep end of the pool”. He was not wrong, but in the years (yes, years) in-between my realization of my trans identity and medically transitioning, I felt I was in a void, too scared to do anything at all.

In looking back, there was no way I would have made it to thirty without taking those steps through the fire. Part of me thought, ‘If not now, when?’ as I worked to book appointments to get approved for HRT. ‘Testing the waters’ while Obama was in office involved a dramatic coming out to family members only to be gaslit that it never happened and also absorbing the reaction to Caitlyn Jenner coming out and knowing if they think she’s a joke, I’m done for (this is all very funny to think about in retrospect as I now detest Caitlyn Jenner in the ways the elder gays in my life detest Andrew Sullivan). Then the world altered. Donald Trump as President of the United States still felt like a fever dream, but my health insurance covered many things tied to a trans masculine gender transition. After years of avoiding the doctor due to trauma unrelated to my gender dysphoria, I took the plunge. I felt isolated but you know, I still had the movies and my friends on my phone. And what were my friends on my phone talking about in 2017? Twin Peaks: The Return.

II. Returns, Rewrites, and Reruns

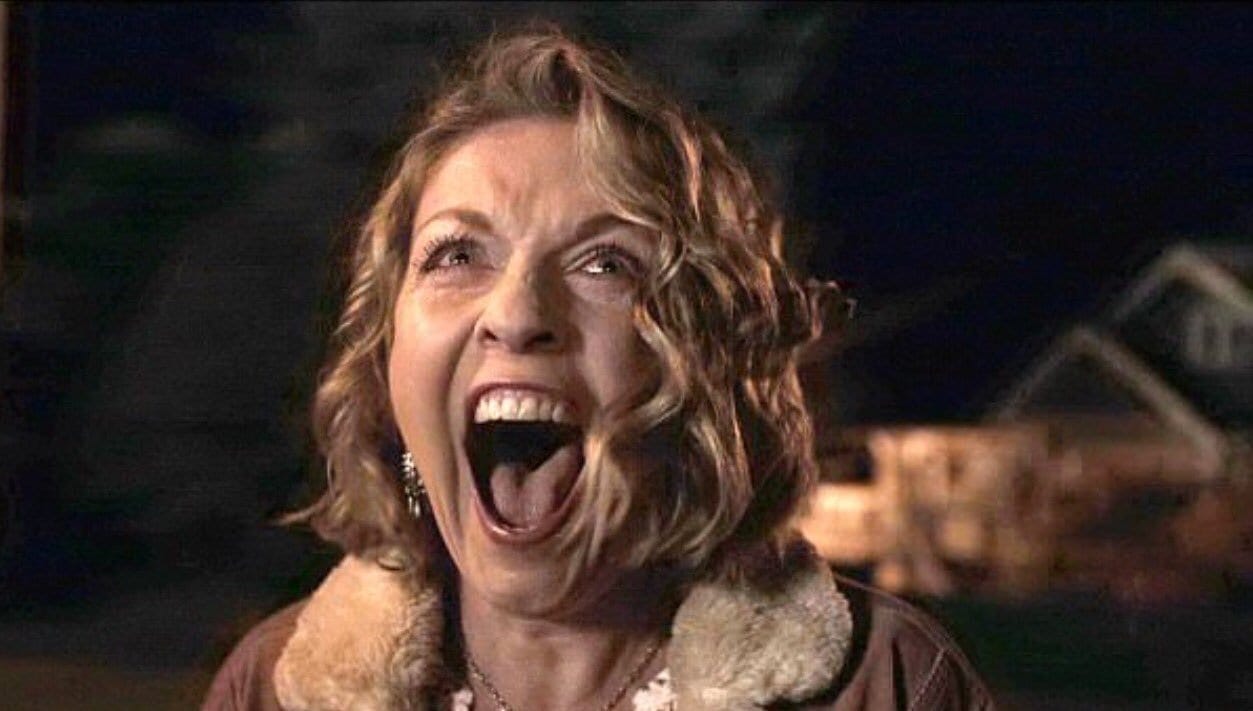

Twin Peaks: The Return still feels like a specific gift from the universe in that truly hellish time for me. I have retreated from declaring it a ‘film’ in that film versus television debate that surrounded all discussions for it at the time, mainly because it was truly the last ritualistic weekly scripted television program I watched. I could never get into any new show that came after it despite a global pandemic rendering me and most of the world a couch potato. Twin Peaks: The Return felt special and experiential not just in the personal viewing experience but the communal experience even though most of my experience with the show was watching alone in my apartment. The one time I went to a watch party of The Return was at film critic Keith Uhlich’s Brooklyn apartment. I remember many things in that episode, such as the lovely Otis Redding needle drop and also the very raw, upsetting moment of Charlene Yi’s character during the music performance at the Roadhouse letting out a violent shriek. That moment would end up being a precursor to an unshakeable moment of horror that ends The Return, which is of the doppelganger of Laura Palmer, Carrie Page (Sheryl Lee), after treating the sight of the Palmer house as an unknown place lets out a blood curdling scream after starting to soak in the atmosphere of it. It occurs after Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan), who took Carrie to the home, thought he changed the course of history in preventing Palmer’s demise.

Twin Peaks: The Return still feels like one of the most consequential works of visual media of the last decade and we are still seeing its influence be filtered in various works, particularly feature films. At the 2023 New York Film Festival, I found myself with a pretty great seat at the New York premiere of Bertrand Bonello’s The Beast. I went in cold. I just heard polarized reactions with the same general response: That shit was crazy.

Bonello, one of my favorite directors working, had long been an admirer of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me and was a noted fan of Twin Peaks: The Return. The impact of those works and Lynch in general have become major inflection points in his work from Nocturama to Zombi Child to Coma to The Beast. The Beast feels the most completely engaged in doing a Twin Peaks: The Return pastiche while also being a pretty unnerving sci-fi dystopia. The Beast in concept sounds reminiscent of Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s Three Times in showing a story of a romance across three periods of time played by the same two actors. But The Beast also shows the aftershocks from the traumas experienced in this central relationship between the characters (played incredibly by Lea Seydoux and George Mackay) that carries into each succeeding relationship that are impacted and informed by what occurred earlier. It is the future. Artificial Intelligence wants to control human behavior and reshape the human race by ‘purifying’ their DNA which is to rid people of their emotions. The Beast raises the question: What if the people you loved in a past life were a dude who sucked. What may be read as ridiculous or goofy as a film premise is actually taken by Bonello and his co-leads into a really haunting and scary prospect of the future. The ending- where in the future, the human race are pretty much life-size ‘dolls’ with a kind of scientifically induced dull expression- has a moment that is reminiscent of the Carrie Page moment in Twin Peaks: The Return. It also made me think of the last episode of my favorite Twin Peaks podcast, The Lodgers, that had on the great film critic Dennis Lim and the great novelist Tom McCarthy where McCarthy quotes literary giant William Faulkner as far as trying to find meaning in the Carrie Page having a haunting that leads one to believe that what happened to Laura cannot be fully wiped. The Faulkner quote is this:

“Between grief and nothing I will take grief.”

Add in Lim’s observation that in many ways Lynch’s love of Vertigo and the denouement of that film about wanting to rewrite the past is shown to not just be futile but retraumatizing and deadly, and I think of Twin Peaks: The Return as having an ending that definitively cautions against rewriting the past. Lynch’s works have always had this this tension with nostalgia, with Lynch’s works clearly being full of manifestations from a different time and place but also always making sure the dark undercurrents of the mid-century Americana experience is exposed and upended for the viewer. Similarly, Bonello has Seydoux’s moment of devastation and realization of what has happened to the world around her in The Beast upend the utopian promises tied to the future. Instead, there has been a regression and retreat from the connectivity and messiness that makes us human.

The film was thrilling and managed to upend a lot of audience expectations where there were screams, gasps, and uncomfortable laughs during the runtime of the film. I watched it at the famously cavernous Alice Tully Hall and, much to my surprise, was sitting behind filmmaker Jane Schoenbrun during this screening of The Beast. We exchanged salutations prior to the film starting but, in retrospect, I am so curious about their reaction to the film. Even beyond what they thought of the film in positive/negative/neutral terms, I was curious how they responded to how Bonello clearly applied aspects of Lynch into his film. Little did I know at the time that Schoenbrun had been in post-production on their film that also was of this lineage to Twin Peaks: The Return. The Beast and I Saw the TV Glow are not so much sister films as they each are disciples to ideas that pervade David Lynch’s work, which is of hauntology and its ripple effects through the lives of their characters. The Beast is more concerned with how the contemporary and near-future of technology is robbing the autonomy of the human element in love and labor, which is itself a commentary on what hovers over film as a medium like a dreaded anvil. I Saw the TV Glow traverses across the potency of nostalgia as Lynch’s, in the film’s case the age of analog media and late 1990s into the 2000s popular culture, and the limits to our attachments of that nostalgia as a safety valve. It is also a film where the trans allegory is text for those of us who are trans in the audience in ways that are immediately understood among us, although that has not dissuaded cis viewers from either attaching their own separate theories to the film or using trans slang like ‘egg cracking’ in their reviews. It helps that Schoenbrun has been upfront with the intentional allegory of the work as well, although cis critics still are furrowing their brows around what this film (especially its ending) all means.

All three of these works all also touch on trauma and the impact it has on our destinies. One of the most fascinating images in Twin Peaks: The Return is of Sarah Palmer (Grace Zabriskie) watching a boxing match knockout over and over again on a loop. Sarah Palmer’s character history is of a woman who lost everything and has been drained of a lot of life in old age. That she is watching images of violence, amid the own violence that occurred in her home, on an endless rerun speaks of the trauma and mania that runs through her decades after her life-altering events. In I Saw the TV Glow, nothing as violent happens to its protagonist Owen (played by Ian Foreman and Justice Smith, respectively), but his grief in losing his mother and aging into a very socially awkward teen and adult is its own unresolved trauma. I Saw the TV Glow has been described as a ‘coming of age’ film but, as Willow and I have discussed the film at length since we have both seen it, Owen does not ‘come of age’. In fact, the very point is he is stifled and stagnated in a way that is this haunting, restless, uncomfortable headspace where Schoenbrun, in my opinion successfully, creates a film that inhabits the aesthetics of dysphoria. Which is why, crucially, I think it is important that Owen is not given a ‘happy ending’ and that his existential crisis remains in limbo. Beyond it mirroring the Pink Opaque television show, the object of his obsession, ending on a cliffhanger, his self-doubt and stillness in being unable to push forward into expressing and acting on his desires, that are so repressed, is something that myself, Willow, and many viewers of the film identified with because we were at one point in our life, Owen.

Jane Schoenbrun has commented on the polarizing ending as this:

“I knew I wanted it to be really honest that just because you’ve now finally seen yourself clearly that the lifetime of damage that repression has instilled in you is going to go away. I don’t view it as a cautionary tale or a definitively sad ending. I just think it’s truthful to the fact that if you've been taught to think of yourself as an impostor or apologize for being yourself, like many trans people are, that instinct doesn’t go away overnight.”

Owen chose not to risk crossing over with the potentially fraught, rough waters in pursuit of embodying the life he has wanted. He chose nothing over grief. He stalled. And as much as those of us who are trans and have transitioned in the many manifestations of being out trans people, many of us have our own moments in our lives of stalling this inevitability. Or, we have witnessed people who stalled their pursuit of this life abruptly even as their yearning to live a new life remained unchanged. This specter of that from I Saw the TV Glow has refused to lose its grip on me since I saw it in the screening room in December of 2023.

III. Trans Narratives That Stall

To look at I Saw the TV Glow as a trans narrative is to also see its ending as a trans narrative that stalls. This has been a point of frustration for many critics who liked the film up to that point and also even queer and trans people who watched the film, regardless of the intentionality of Schoenbrun. The film is a radical departure from a trans narrative that many of us both in the trans community and outside of the trans community have been conditioned to watch, which is usually the pedantic transition narrative of before and after. Most trans people have bristled at this narrative’s dominance in media about us and in Schoenbrun’s case, the film is decidedly not having Owen inhibit that space.

When I mention that Owen’s narrative of stalling is not uncommon in the trans experience, I think of not just of my peers who have struggled with their gender identity but from researching trans magazines, publications, ephemera, and oral histories of people who came into the world in a more precarious, stifling, conforming, cis-heteronormative culture. We look back at trans history, especially with the moving image, being linked to Christine Jorgensen who served as the model and icon of the innovations of transition. But Jorgensen was made an anomaly for years by the media and by the early gatekeepers around trans health who saw being a transsexual as a rarity that must remain rare. Many trans elders I know experienced stalling by way of these gatekeepers who turned them away from moving forward on their transitional care often ranging from being ‘too successful’ in their careers to be considered somebody with a disorder or due to their sexual preference and so on. There were also trans people of a certain age who discreetly straddled into two different worlds: one was their ‘typical’ life suburbia, white picket fences, and the nuclear family and the other of living their ‘second self’ among crossdressing groups, retreats, and newsletters where they can express this side of themselves. The best representation that I see of this particular kind of trans experience is the Sebastien Lifshitz documentary on Casa Susanna where there are trans women who ultimately transitioned despite initially identifying as crossdressers while there were those froze at the prospect of transition were tied to their fears of losing everything if they ever publicly disclosed and attempted to move forward in living as women. These anxieties did not just take a toll on these individuals but also trickled into their marriages and family life. Some took their own lives in being overwhelmed in these difficulties and it still persists today.

In the age of visibility politics, I notice people find these stories antithetical to those politics and at best serve as a placeholder for the past to show how far the world has progressed. I disagree. I find these stories valuable and necessary as far as looking at human stories that show the tolls and pressures around why many of us stay in the closet. I consider Owen’s story in I Saw the TV Glow to run closer to this fraught straddling. Similarly, people will find the fact that others and I call it a trans narrative to be antithetical to the concept of transness on-screen in being absent of a physical progression of the character and that the film is leaning on Schoenbrun’s trans authorship for it to be seen as a trans story. But there is one and it resides in the second most prominent character of the film.

The character who does offer something closer to the typical progression of a trans narrative is Maddy (Brigiette Lundy-Paine) who, like Owen, is consumed by the Pink Opaque and briefly disappears from the narrative only to return, almost like a ghost but also looking even more androgynous than they were before. She tells Owen she has been in the world of the Pink Opaque. Maddy’s life story is tied to her queerness and abusive household. She becomes so invested in living the Pink Opaque that she tries to shadow its darkest elements, including allowing herself to be buried alive. Abuse, depression, isolation, migration, and suicide ideation make up a lot of Maddy’s character, yet her pain feels less dread-inducing as say many tragic trans characters in cinema history (think Elvira in Fassbinder’s In a Year of 13 Moons or Brandon Teena in Boys Don’t Cry). She’s mysterious and despite her aesthetic as the typical 90s-00s alt girl, she is not some jaded, disaffected, nihilistic youth. She becomes a lodestar for Owen. Maddy offers him a space to watch Pink Opaque via VHS tapes and screenings at her house. There is no aimlessness to Maddy. She pursues what she wants with a purpose even at the risk of her own annihilation. People think she is crazy to do it and she has been left to her own devices. Her trans narrative is the more relatable one and one that Schoenbrun withholds from viewers because Owen’s trepidation keeps him at a distance, preferring to look at the world from his television screen.

IV. Projections

Television as medium comes up in I Saw the TV Glow reviews, although it is more in the intended analogies Pink Opaque has to real-life shows like Buffy: The Vampire Slayer in not just dealing with the YA paranormal but also quite effectively aping the aesthetics of what a network television show for teens looks like. However, I have to say I was not really thinking about those shows because I was not as into them as others in my generation. What I did think about was how in the mid-twentieth century with the birth of the television medium is intertwined with the Jorgensen trans iconography. Jorgensen’s life story- that would be introduced to the world during the Eisenhower administration and would persist even after her death in the late 1980s- proliferated American culture because her visibility was not just published in print but broadcasted on screens that were broadcast across America and the world. In our book, we call Jorgensen a legend mainly because her influence took over so much of the narrative of being trans even if she was not the first American to get what would be called ‘gender-affirming care’. But she had the talk show circuit, others did not. There is something in how there are utopian notions at the start for both television and Christine Jorgensen’s celebrity as a trans woman in that the possibilities are being transmitted and seen by millions. However, television was a medium of limitations.

Much of television’s purpose was about selling products and the novelty of seeing something you had never seen before quickly waned in the limits of television networks, time on air, and censorship. Similarly, Jorgensen retained her legend as the trans phenomenon because of how the media portrayed her among a very small group of individuals, which effectively capped what people could see about trans embodiment in the years and decades since her public spectacle. The trans image in television broadcast form has always been limited and mostly hidden, some of it out of censorship and in other instances fear of putting yourself out there due to negative repercussions. And so this common question of where our self-actualization came from comes up. How did we ‘know’ if there was no direct link to visibility unlocking that for us?

In recently talking to Vera Drew of The People’s Joker, she notes that we were all given Batman toys as children but it was less tied to conforming with the monoculture and more about how we applied our imagination in playing with these action figures, which in her case helped unlock her queer and trans identities. I think our projections as trans people onto our early pop culture obsessions are still very clear for many of us because it is tied to a certain self-actualization of who we wanted to be. And frankly, I feel like I carried those cultural obsessions well into adulthood. While I have always argued that Don Draper is a trans-coded character, I do think while Mad Men was on the air that my obsession with the show became very loaded in how much I made this show my outlet during a very difficult time in my life when I was grappling with my gender identity and being closeted. The trans iconography of Laura Palmer from Twin Peaks feels much more broadly discussed these days that are tied to a certain martyrdom and tragedy of her character that trans adult viewers connect to with their sense of loss of identity, abuse, and the fear of being harmed. The projections can certainly vary in their mileage from viewer to viewer, but I think what Drew, Schoenbrun, and many other trans filmmakers have presented in their films are in the absence of a trans experience, we train ourselves to search for other forms of media that can be both aspirational and revealing of ourselves.

I see no cautionary tales consigned to Owen or Maddy’s cultural obsession with Pink Opaque in the film by Schoenbrun, but Maddy went further and took more risks in whatever that show unlocked within her while Owen has wavered not just in his willingness to follow Maddy as a fellow traveler into the show’s world, but entering a stage of denial in the show’s importance on his life. He watches Pink Opaque in reruns and dislikes it, finding it cheesy and poorly aged as a show. The nostalgia is wiped away, but it goes deeper. His original gender projections towards the show are now self-loathing projections in wanting to distance himself from what gave him a sense of unease that he also previously could not look away from. Often trans people are embarrassed in ever revealing what was the possible pop cultural root of what they aspired to be and it is likely something objectively embarrassing because most entertainment aimed at kids and teenagers are just that. But that should not dissuade somebody from living out their life or at least trying to live that life. If there is a cautionary tale in I Saw the TV Glow, it is how easily Schoenbrun shows Owen push the things that made up so much of his existence away and frankly deny any sense of wonder and joy he got from it.

I do not begrudge people who ended up being flummoxed about what this film was doing, found it too alienating, and felt like there could have been more to say, but to me this expands on Schoenbrun’s predilections in showing how technology, entertainment, and alienation can be linked to a certain trans adolescence for their generation. I saw myself in Casey, the protagonist in Schoenbrun’s previous feature, We’re All Going to the World’s Fair. I also saw a bit of myself in Owen in I Saw the TV Glow. Whether being out of body or in a stasis, it can feel like a psychological prison, especially when you now know the answer to what is happening to you.

My only regret in transitioning was that I did not do it sooner. I soon realized at a certain point there was no virtue found in beating myself up. It became about having the urgency of finally doing it and to finally live. I can reconcile with my past, but I also look at the past as smudge inhabited by a shell of a person who felt helpless. This is where I see Owen.

Delighted to have had you at that watch party, Caden. Equally so to read your thoughts on all these works.

I read this before I saw the film, saw it last night and wanted to come back and say this is a wonderful review!!